extract forceconstants

Short description

The main algorithm of the TDEP method. Starting with a symmetry analysis, this code finds the irreducible representation of interatomic forceconstants and extracts them from position and force data.

Command line options:

Optional switches:

-

--secondorder_cutoff value,-rc2 value

default value 5.0

Cutoff for the second order force constants -

--thirdorder_cutoff value,-rc3 value

default value -1 mutually exclude "--thirdorder_njump"

Cutoff for the third order force constants -

--fourthorder_cutoff value,-rc4 value

default value -1 mutually exclude "--fourthorder_njump"

Cutoff for the fourth order force constants -

--stride value,-s value

default value 1

Use every N configuration instead of all. Useful for long MD simulations with linearly dependent configurations. -

--firstorder

default value .false.

Include the first order force constants. These can be used to find the finite temperature equilibrium structure. -

--residualfit

default value .false.

Fit the second order first, then the higher orders to the residual. -

--readforcemap

default value .false.

Readinfile.forcemap.hdf5from file instead of calculating all symmetry relations. Useful for sets of calculations with the same structure. -

--readirreducible

default value .false.

Read the irreducible forceconstants frominfile.irrifc_*instead of solving for them. This option requires aninfile.forcemap.hdf5, as above. -

--potential_energy_differences,-U0

default value .false.

Calculate the difference in potential energy from the simulation and the forceconstants to determine U0. As referenced in the thermodynamics section of phonon dispersion relations this is the renormalized baseline for the TDEP free energy: $$U_0= \left\langle U^{\textrm{BO}}(t)-\frac{1}{2} \sum_{ij}\sum_{\alpha\beta} \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} \mathbf{u}^{\alpha}_i(t) \mathbf{u}^{\beta}_j(t) \right\rangle$$ This number should be added to the appropriate phonon free energy. -

--printforcemap

default value .false.

Printoutfile.forcemap.hdf5for reuse. -

--polar

default value .false.

Add dipole-dipole corrections for polar materials. -

--polarcorrectiontype value,-pc value, value in:1,2,3

default value 3

What kind of polar correction to use. -

--help,-h

Print this help message -

--version,-v

Print version

Examples

extract_forceconstants -rc2 5.1

extract_forceconstants -rc2 4.5 -rc3 3.21

Longer summary

Calculations of the interatomic force constants are the most important part of any lattice dynamics calculation as they are used to calculate many micro and macroscopic properties of the system, e.g. phonon, thermodynamic, and transport properties, etc. This codes takes sets of displacements and forces, and uses these to fit the coefficients in an effective lattice dynamical Hamiltonian. This is by no means a new idea.1 The main advantage of the TDEP method is in the implementation: it is numerically robust, well tested and general. It is not limited in order, nor limited to simple ordered systems.

Lattice dynamics and interatomic force constants

A quick recap of lattice dynamical theory:2 a displacement $\mathbf{u}$ of an atom $i$ from its ideal lattice position changes the potential energy of the lattice. Temperature disorders the lattice, causing all atoms to be displaced from their equilibrium positions; this effect can be modeled as a Taylor expansion of the potential energy contribution of the instantaneous positions of the atoms in the system, i.e. $U=U({ \mathbf{r} })$. It is convenient to define the atomic positions as displacements $\mathbf{u}$ from their equilibrium positions $\mathbf{R}_i+\boldsymbol{\tau}_i$.

$$ \begin{equation} \textbf{r}_i=\mathbf{R}_i+\boldsymbol{\tau}_i+\mathbf{u}_i. \end{equation} $$

$\mathbf{R}_i$ is a lattice vector and $\boldsymbol{\tau}_i$ is the position in the unit cell. We can then expand the potential energy in terms of displacements as:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} U(\{\textbf{u}\})=& U_0+ \sum_{i}\sum_\alpha \Phi^\alpha_{i} u^\alpha_{i} + \frac{1}{2!} \sum_{ij} \sum_{\alpha\beta} \Phi^{\alpha\beta}_{ij} u^\alpha_{i} u^\beta_{j} + \\ + & \frac{1}{3!} \sum_{ijk} \sum_{\alpha\beta\gamma} \Phi^{\alpha\beta\gamma}_{ijk} u^\alpha_{i} u^\beta_{j} u^\gamma_{k}+ \frac{1}{4!} \sum_{ijkl} \sum_{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta} \Phi^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta}_{ijkl} u^\alpha_{i} u^\beta_{j} u^\gamma_{k} u^\delta_{l} + \ldots \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Here, $\alpha\beta\gamma\delta$ are Cartesian indices and $U_0$ is the potential energy of the static lattice. The coefficients of the Taylor expansion are the derivatives of the potential energy with respect to displacement and are called the Born-von Kàrmàn force constants, which can be expressed as tensors of increasing rank:

$$ \begin{align} \Phi^\alpha_i & = \left. \frac{\partial U}{\partial u_i^\alpha} \right|_{u=0} = 0 \\ \Phi^{\alpha\beta}_{ij} & = \left. \frac{\partial^2 U}{\partial u_i^\alpha \partial u_j^\beta} \right|_{u=0} \\ \Phi^{\alpha\beta\gamma}_{ijk} & = \left. \frac{\partial^3 U}{\partial u_i^\alpha \partial u_j^\beta \partial u_k^\gamma} \right|_{u=0} \\ \Phi^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta}_{ijkl} & = \left. \frac{\partial^4 U}{\partial u_i^\alpha \partial u_j^\beta \partial u_k^\gamma \partial u_l^\delta} \right|_{u=0} \end{align} $$

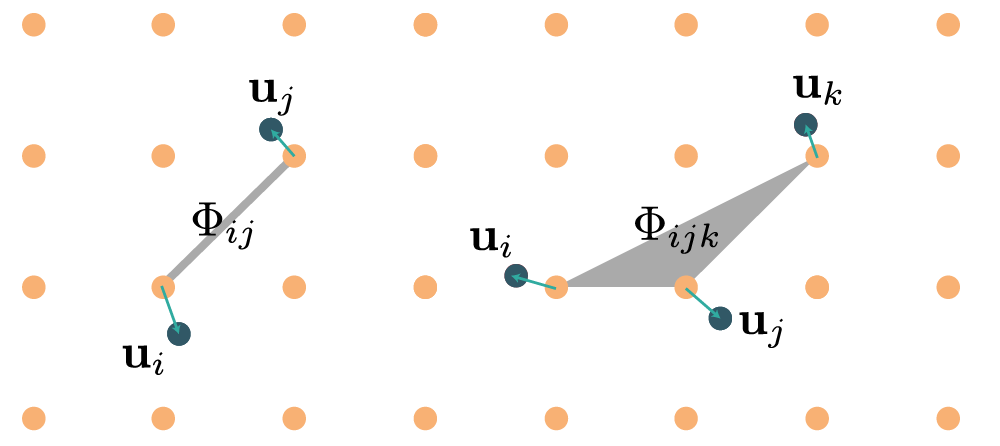

By increasing rank, the force constants of rank $n$ represent $n$-body interactions, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Force constant symmetries

Symmetry analysis allows us to greatly reduce the number of values needed to express the force constants (by multiple orders of magnitude, discussed more below) and is therefore crucial for generalizing the TDEP to include higher order terms in the potential energy surface. The symmetries of the force constants are deduced from rotational and translational invariance of the system, in addition to the symmetries of the crystal itself. We start with the transposition symmetries, which is an invariance under the permutation of the indices:43

$$ \begin{align} \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} & = \Phi_{ji}^{\beta\alpha} \\ \Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\gamma} & = \Phi_{jik}^{\beta\alpha\gamma} = \ldots \\ \Phi_{ijkl}^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta} & = \Phi_{jikl}^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta} = \ldots \end{align} $$

All lattices belong to one of the 230 lattice space groups. The force constants should be invariant under these symmetry operations. If two tensors are related by symmetry operation $S$ their components are related as follows:

$$ \begin{align} \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} &= \sum_{\mu\nu}\Phi_{kl}^{\mu\nu} S^{\mu\alpha}S^{\nu\beta} \\ \Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\gamma} &= \sum_{\mu\nu\xi}\Phi_{mno}^{\mu\nu\xi} S^{\mu\alpha} S^{\nu\beta} S^{\xi\gamma}\\ \Phi_{ijkl}^{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta} &= \sum_{\mu\nu\xi\kappa}\Phi_{mnop}^{\mu\nu\xi\kappa} S^{\mu\alpha} S^{\nu\beta} S^{\xi\gamma} S^{\kappa\delta} \,.\\ \end{align} $$

where $S^{\alpha\beta}$ is the proper or improper rotation matrix of the symmetry operation $S$. Naturally, this will also enforce the periodic nature of the lattice. Force constants also obey the translational invariance (acoustic sum rules):

$$ \begin{align} \sum_j \mathbf{\Phi}_{ij} & =0 \quad \forall\, i \\ \sum_k \mathbf{\Phi}_{ijk} & =0 \quad \forall\, i,j \\ \sum_l \mathbf{\Phi}_{ijkl} & =0 \quad \forall\, i,j,k \end{align} $$

The rotational invariance gives

$$ \begin{align} \sum_i \Phi_i^\alpha r_i^\beta & = \sum_i \Phi_i^\beta r_i^\alpha \quad \forall \, \alpha,\beta \\ \sum_j \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} r_j^\gamma + \Phi_i^\beta \delta_{\alpha\gamma} & = \sum_j \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\gamma} r_j^\beta + \Phi_i^\gamma \delta_{\alpha\beta} \quad \forall \, \alpha,\beta,\gamma \\ \sum_k \Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\gamma}r_k^\lambda + \Phi_{ij}^{\gamma\beta} \delta_{\alpha\lambda} + \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\gamma} \delta_{\beta\lambda} &= \sum_k \Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\lambda}r_k^\gamma + \Phi_{ij}^{\lambda\beta} \delta_{\alpha\gamma} + \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\lambda} \delta_{\beta\gamma} \quad \forall \, \alpha,\beta,\gamma,\lambda \\ \end{align} $$

And finally, the Huang invariances

$$ \begin{align} [\alpha\beta,\gamma\lambda] & = \sum_{ij} \Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} r_{ij}^\gamma r_{ij}^\lambda \\ [\alpha\beta,\gamma\lambda] & = [\gamma\lambda,\alpha\beta] \end{align} $$

ensure that the second order forceconstants, when taken to the long-wavelength limit, result in the correct number of elastic constants. For low-symmetry crystals the Hermitian character of the dynamical matrix is enforced:98

$$ \begin{equation} \sum_{j \ne i} \Phi^{\alpha\beta}_{ij} = \sum_{j \ne i} \Phi^{\beta\alpha}_{ij} \quad \forall\, i \end{equation} $$

All the symmetry relations above are naturally satisfied by the force constants produced by this code.

Effective Hamiltonian

The traditional lattice dynamical Hamiltonian described above has severe limitations, in that it's deduced from the derivatives of zero temperature configuration of the crystal. The form of the Hamiltonian is however beneficial: the second order forceconstants produce an exactly solvable Hamiltonian and with phonon quasiparticles, and the higher order terms can be treated as perturbations. To extend the usefulness of this Hamiltonian, we give up the constraint that the force constants are derivatives of the zero temperature configurations. Instead, the force constant tensors are just parameters in an effective Hamiltonian that are left to be determined.

Schematically, self-consistent or effective phonon theories can be split into two parts: the first part is revolves around how to sample the Born-Oppenheimer surface, the second part around how to use that data to produce an effective Hamiltonian.

Sampling phase space

The most straightforward way to sample the Born-Oppenheimer surface is to use molecular dynamics. This can be costly, although I provided some tools to make it faster: parallelizing over different random seeds combined with selective upsampling certainly makes it feasible. For systems with significant nuclear quantum effects, path integral molecular dynamics is preferred. The cost of these can be quite significant, but similar acceleration techniques can be used.

If you care predominantly about speed, stochastic sampling might be preferred. The way the Born-Oppenheimer surface is sampled does not influence the TDEP algorithms in any way. I even consider stochastic sampling using the zero-point the preferred way of calculating the true zero temperature force constants. The only thing required of the sampling is that it provides a set of forces, $\mathbf{f}^{\textrm{BO}}$, and displacements $\mathbf{u}$.

Obtaining an effective Hamiltonian

The basic premise is to use a model Hamiltonian (where orders beyond pair interactions are optional) given by

$$ \begin{equation}\label{eq:hamiltonian} \hat{H}= U_0+\sum_i \frac{\textbf{p}_i^2}{2m_i}+ \frac{1}{2!}\sum_{ij} \sum_{\alpha\beta}\Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta} u_i^\alpha u_j^\beta +\frac{1}{3!} \sum_{ijk} \sum_{\alpha\beta\gamma}\Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\gamma} u_i^\alpha u_j^\beta u_k^\gamma \ldots \end{equation} $$

and match the forces of the model, $\mathbf{f}^{\textrm{M}}$ to $\mathbf{f}^{\textrm{BO}}$.7,6,5 A brute force minimization is certainly possible, but the current implementation is a bit more sophisticated. The forces of the model Hamiltonian are given by

$$ \begin{equation} f^{\mathrm{M}}_{i\alpha}= -\sum_{j\beta}\Phi_{ij}^{\alpha\beta}u_j^\beta -\frac{1}{2}\sum_{jk\beta\gamma}\Phi_{ijk}^{\alpha\beta\gamma}u_j^\beta u_k^\gamma + \ldots \end{equation} $$

To exploit the symmetry relations, we populate each tensor component with a symbolic variable, called $\theta$. The index $k$ runs from 1 to the total number of components in all tensors. We include all tensors within a cutoff radius $\textbf{r}_c$ (the maximum cutoff is determined by the simulation cell size). Using symmetries we figure out which tensor components are unique by accounting for those components that are either 0 or equal to another tensor component. This drastically reduces the number of values that have to be determined. With the symmetry irreducible representation at hand, we express the forces in the model Hamiltonian:

$$ \begin{equation} f^{\mathrm{M}}_{i\alpha}= \sum_k \theta_k c_k^{i\alpha}(\mathbf{U}). \end{equation} $$

Here $c_k^{i\alpha}(\mathbf{U})$, the coefficient for each $\theta_k$ is a polynomial function of all displacements within $\textbf{R}_c$. The form of this function depends on the crystal at hand (see the minimal example below). For a given supercell, we can express the vector of all forces in the cell as a matrix product:

$$ \begin{equation} \underbrace{\mathbf{F}^{\mathrm{M}}}_{3N_a \times 1}= \underbrace{\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u})}_{3N_a \times N_{\theta}} \underbrace{\mathbf{\Theta}}_{N_{\theta} \times 1} \end{equation} $$

where the underbraces denote size of the matrices. The coefficient matrix $\mathbf{C}$ is a function of all the displacements in the supercell. $\mathbf{\Theta}$ is a vector holding all the $\theta_k$. Then we seek the $\mathbf{\Theta}$ that minimizes the difference between the model system and the ab initio one:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \min_{\Theta}\Delta \mathbf{F} & = \frac{1}{N_c} \sum_{c=1}^{N_c} \left| \mathbf{F}_c^{\textrm{BO}}-\mathbf{F}_c^{\textrm{M}} \right|^2= \\ & =\frac{1}{N_c} \sum_{c=1}^{N_c} \left| \mathbf{F}_c^{\textrm{BO}}-\mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u}_{c})\mathbf{\Theta} \right|^2 = \\ & = \frac{1}{N_c} \left\Vert \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{F}_1^{\textrm{BO}} \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{F}_{N_c}^{\textrm{BO}} \end{pmatrix}- \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u}_1) \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u}_{N_c}) \end{pmatrix} \mathbf{\Theta} \right\Vert \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Here $N_c$ is the number of supercell configurations used to sample the Born-Oppenheimer surface. A least squares solution,

$$ \begin{equation} \mathbf{\Theta}= \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u}_1) \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{u}_{N_c}) \end{pmatrix}^{+} \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{F}^{\textrm{BO}}_1 \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{F}^{\textrm{BO}}_{N_c} \end{pmatrix} \end{equation} $$

gives the $\mathbf{\Theta}$ that minimizes these forces. Then, with a simple substitution back into \(\mathbf{\Phi}_{ij}\) and $\mathbf{\Phi}_{ijk}$ we determine the quadratic and cubic force constants. Note all orders of force constants are extracted from the same set of displacements and forces, simultaneously.

Illustration of the symmetry constrained solver

Even for a simple system, such as fcc Al, the matrix $\mathbf{C}$ is in general far too large to print in a meaningful way. I will try to explain the algorithm more schematically: suppose we want to determine the coefficients for a single second order force constant:

$$ \begin{equation*} \mathbf{\Phi}= \begin{pmatrix} \theta_1 & \theta_2 & \theta_3 \\ \theta_4 & \theta_5 & \theta_6 \\ \theta_7 & \theta_8 & \theta_9 \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation*} $$

using a number of displacements and forces. The 9 unknown variables suggest we need at least 9 equations, preferrably more to make the equations overdetermined. With four samples, each providing a force and a displacement, we get

$$ \begin{equation*} \begin{pmatrix} f^1_x & f^1_y & f^1_z \\ f^2_x & f^2_y & f^2_z \\ f^3_x & f^3_y & f^3_z \\ f^4_x & f^4_y & f^4_z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} u^1_x & u^1_y & u^1_z \\ u^2_x & u^2_y & u^2_z \\ u^3_x & u^3_y & u^3_z \\ u^4_x & u^4_y & u^4_z \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \theta_1 & \theta_2 & \theta_3 \\ \theta_4 & \theta_5 & \theta_6 \\ \theta_7 & \theta_8 & \theta_9 \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation*} $$

which can be solved with a pseudoinverse. However, using the symmetry relations we know that the force constants are not all independent, they could have the following form:

$$ \begin{equation*} \mathbf{\Phi}= \begin{pmatrix} \theta_1 & \theta_2 & 0\\ \theta_2 & \theta_1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \theta_1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation*} $$

Taking the product of the displacement matrix and the force constant matrix yields

$$ \begin{equation*} \begin{pmatrix} f^1_x & f^1_y & f^1_z \\ f^2_x & f^2_y & f^2_z \\ f^3_x & f^3_y & f^3_z \\ f^4_x & f^4_y & f^4_z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} u^1_x\theta_1+u^1_y\theta_2 & u^1_y\theta_1+u^1_x\theta_2 & u^1_z\theta_1 \\ u^2_x\theta_1+u^2_y\theta_2 & u^2_y\theta_1+u^2_x\theta_2 & u^2_z\theta_1 \\ u^3_x\theta_1+u^3_y\theta_2 & u^3_y\theta_1+u^3_x\theta_2 & u^3_z\theta_1 \\ u^4_x\theta_1+u^4_y\theta_2 & u^4_y\theta_1+u^4_x\theta_2 & u^4_z\theta_1 \end{pmatrix} \end{equation*} $$

That can in turn be rewritten as

$$ \begin{equation*} \begin{pmatrix} f^1_x \\ f^1_y \\ f^1_z \\ f^2_x \\ f^2_y \\ f^2_z \\ f^3_x \\ f^3_y \\ f^3_z \\ f^4_x \\ f^4_y \\ f^4_z \end{pmatrix}= \begin{pmatrix} u^1_x && u^1_y \\ u^1_y && u^1_x \\ u^1_z && 0 \\ u^2_x && u^2_y \\ u^2_y && u^2_x \\ u^2_z && 0 \\ u^3_x && u^3_y \\ u^3_y && u^3_x \\ u^3_z && 0 \\ u^4_x && u^4_y \\ u^4_y && u^4_x \\ u^4_z && 0 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \theta_1 \\ \theta_2 \end{pmatrix} \end{equation*} $$

We now have an equation in only the independent components, expressed as a vector of forces, a coefficient matrix and a vector of irreducible forceconstants. In a real system, these equations are built exactly the same way, but for all forceconstants of all orders simultaneously. All the forceconstants are determined from a single set of equations.

This numerical solver is remarkably stable. Other schemes determine the components one by one, and must later modify the values to comply with the symmetry of the lattice, lending some ambiguity to the results. With this scheme, there is no need to carefully displace atoms one by one, just displace all of them. This is numerically beneficient, numerical noise will be averaged out.